I’m a ruminator. And that’s my excuse for not regularly posting on Substack. Maybe it’s also why I consume social media across multiple platforms, but rarely post for myself.

Sometimes I feel that when I finally have an appropriate response to something I’ve read, it’s too late. The moment has passed. Everybody has moved on. But an article has been on my mind since I first read it over a month ago, so I thought it was time to stop ruminating and actually write about it.

In the Vox article “Your Brain is Lying to You About the Good Old Days,” Bryan Walsh wrote, “Much of the world is gripped by a politics of nostalgia, one grounded in the assumption that we have to turn back time to a moment when everything was better.”

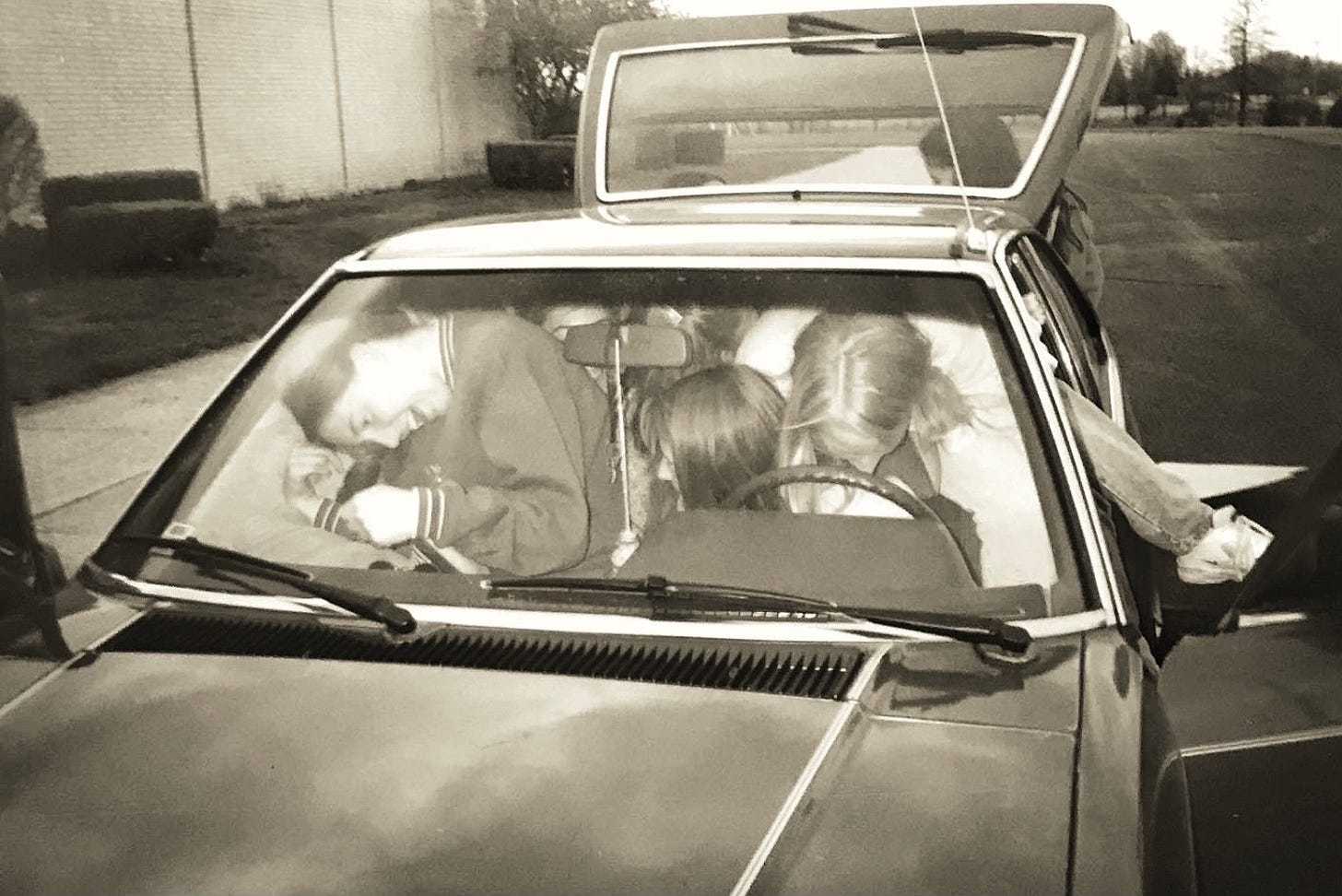

Let me start by saying that I love to reminisce. Get me in a room with my high school friends and we’ll soon start sharing stories about how we would scare ourselves by visiting a century-old cemetery that literally stood in the middle of a dirt road and was surrounded by folklore that generations passed down to the next (my grandfather to my father, my father to me). Or the time we squeezed 18 teenagers into my 1983 Honda Accord hatchback for an American history lesson as a way of recreating how people stuffed phone booths in the 1950s (and we think TikTok trends are weird). Then of course there was the time we were late for tennis practice, were speeding along a back road, and, as we crested a small hill, the car launched into the air. Don’t worry; we landed on all fours and were fine, though the driver needed a moment to recover. (And now I’m realizing how rural of an upbringing I had that most of my memories involve cars and back roads, but I digress…)

Nostalgia is fun. But it can also lie to us.

As Walsh said, “Our brains help deceive us. Thanks to ‘selective memory,’ humans have a tendency to forget negative events from the past and reinforce positive memories. It’s one reason why our feelings and memories about the past can be so inaccurate — we literally forget the bad things and give the good things a nice, pleasant glow. The further back the memory goes, the stronger that tendency can be.”

One of my all-time favorite TV quotes comes from The Office finale when the character Andy Bernard said, “I wish there was a way to know you’re in the good old days before you actually left them.”

But what if the good old days weren’t as good as we thought? What if our selective memory paints a sepia-tone picture of the “good” while washing away the full, four-color image that also included shading. Gradation. Variation. Nuance.

I often say that I did not set out to write historical fiction. Everything I wrote in college and as I fumbled my way through two practice novels was modern and contemporary. The reason my debut novel (The Last Carolina Girl) is historical is because of a personal connection I have to the subject matter. I learned that a great aunt of mine had been sterilized by the state of Indiana when she was an adolescent. This woman—one of the sweetest, kindest, most caring people I have ever known—never lost her desire to be a mother in her nine decades of life. But she wasn’t able to decide for herself if she would have biological children.

I couldn’t make sense of why that could’ve happened to her. I needed to know how that was ever legal within our nation. And it was. In 1927 the Supreme Court ruled in favor of eugenicists, upholding their right to forcibly sterilize individuals. It’s estimated that 60,000 to 70,000 were sterilized within the United States from 1907 to 1983.

Or, let’s jump ahead to the mid 1960s (The Girls We Sent Away). A time full of perfect nuclear families, smiling housewives, and obedient children. Oh, and also an era when maternity homes were places to hide away teenage daughters when they dared to bring shame on their family by becoming pregnant out of wedlock. And in pursuit of covering up their misdeed, some of these homes coerced and manipulated them into signing over their babies for adoption even if the mothers very much wanted to keep those children.

There was also the 1950s (The Mad Wife) when housewives found fulfillment doting on their husbands and spending their days rearing their children alone, surrounded by modern conveniences meant to simplify their lives. And if they couldn’t find fulfillment, then they could find contentment through mild tranquilizers. Or electroconvulsive therapy. Or perhaps lobotomy if she was particularly melancholic or hysterical.

Like Andy Bernard, I like to look back on my good old days when the only care in the world I had was if my friends and I had enough gas money, if our parents would let us stay out late enough, or if we could outrun the ghost that Steve swore he saw lurking behind the tombstone.

Nostalgia is fun. But it’s not always the full picture. Sepia is a beautiful overlay, but sometimes we need to remember the full, four-color image even if it reminds us of things we’d rather forget. Perhaps especially then.

And this is why stories matter. They have the potential to bring that picture into full color, to remind us of the nuances, and to call us to better understanding and empathy.

“I truly admire Church’s writing. But what I admire even more is her willingness to see that which most ignore.” ~ frenchybookworm via IG.

If you’d like to read my stories for yourself, find them at your favorite bookseller, or here’s a handy link for you:

Meagan this is so true. I’m not sure if we forget the bad parts to protect ourselves or because something is pushed out when we store something else. 🤪